How Can We Become More Creative about Housing?

Share this

Paul Smith (centre) at the celebrations outside one of the first houses to be built by We Can Make. Credit: WeCanMake

Pam Beddard interviews Paul Smith, CEO of Elim Housing and former Cabinet member for housing, Bristol City Council about creative bureaucracies and housing.

This year, for the first time in the 12-year history of the round-up, Bristol failed to make it into The Sunday Times’ annual guide to the Best UK Places To Live, a list the city has previously topped.

A key reason given for the omission was the city’s ‘pitiless property market’, a decision backed by long and loud local complaints from many quarters about spiralling house prices/ rents; the shortage of rented accommodation; shock endings of tenancies; and rising cases of homelessness.

Numerous plans or projects are attempting to address the issue, usually from the biggest names in UK house-building and very often sparking controversy – about the height of tower blocks; ugly design; carbon costs, traffic impacts; the loss of green spaces, wildlife habitats and/or iconic views; over-focus on student flats and, once planning consent has been given, pleas from the developers to reduce the agreed percentage of affordable units.

Less voiced, though, is whether enough imagination is being shown in approaches to the housing problem and if so, why not?

Paul Smith, CEO of the social housing charity Elim Housing Association and a former Bristol City councillor who served as the Cabinet member for housing, is not alone in thinking more support is needed for smaller-scale, community-led, answers.

They, however, face special challenges.

‘It’s not just me but most people in the housing sector are struggling with increased bureaucracy and time-consuming regulations. The rules say planning applications should be processed within eight weeks, but you’d be lucky if this happened within eight months and often much longer.’

‘One reason for the delays is that the planning system is increasingly expected to solve all the world’s problems. This translates into a requirement for a vast array of surveys/ reports – on biodiversity, ecology, archaeology, design aesthetics, traffic, flood risk and so on.

‘None of this is bad but the time and cost involved is a huge barrier to progress and greatly disadvantages small scale developments and self-builds. It’s really only the very big developers who can get through it all cost-effectively’.

The regulations are another barrier.

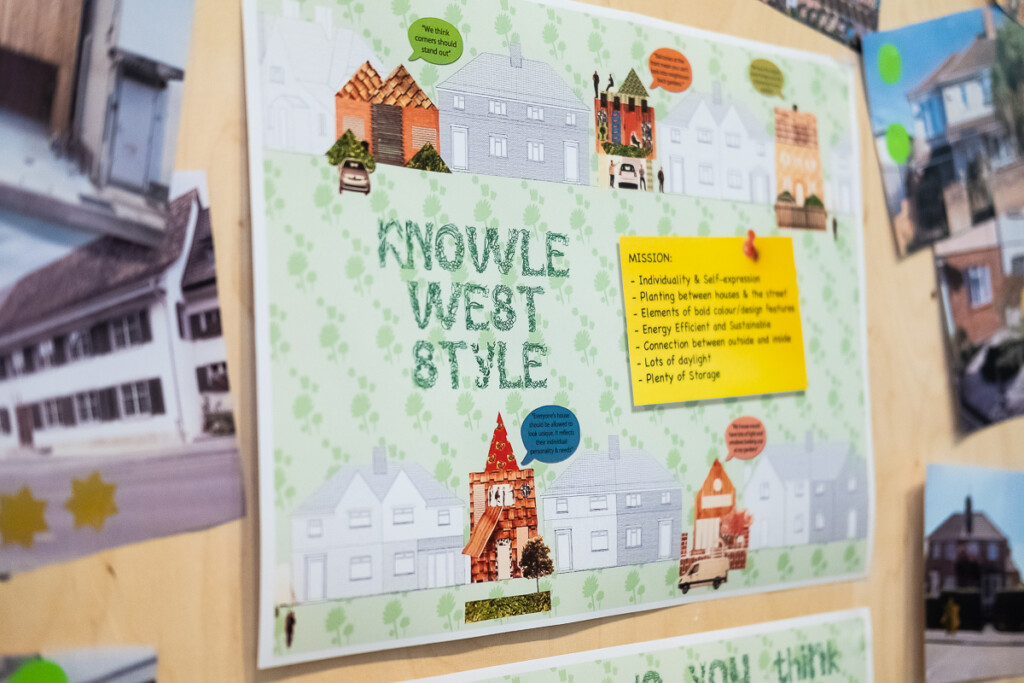

For instance, through a neighbourhood testbed project We Can Make, the people of Knowle West have identified 1500 sites within the area capable of taking new one or two bedroom homes.

Knowle West Community Design Code. Credit: Alistair Campbell + WeCanMake

Many would involve making use of the large and, for some, potentially burdensome back gardens which are common features of interwar housing estates, not just in Bristol but throughout the country.

‘Imagine,’ says Smith, ‘if we could ramp this up nationwide, how many new homes we could create.’

The We Can Make playbook offers a vision of the possibilities, based on only 10% of potential micro-sites being used. It points to 150 new homes in Knowle West; 33,000 if replicated in similar council-built estates in other UK places; a total of 100,000 if market-built estates are factored in.

Yet Bristol City Council (BCC), like many others, has explicit planning policies controlling “back land development”, AKA “garden grabbing”.

As a result, only two homes have been created so far and these only after creative collaboration by We Can Make and council officers and an agreement that the land will remain in community-ownership forever and the properties must stay ‘affordable’.

John’s home in the garden of Bill’s council house. Credit: Ibolya Feher + WeCanMake

BCC has now agreed to extend We Can Make’s remit to all of south Bristol but Paul Smith believes a roll-out of the Knowle West blueprint to similar estates up and down the country could halt the decline very many older UK estates are experiencing.

‘These estates were built for families, but kids grow up, move away, the population ages and declines with knock on effects on pubs, shops, services. Allowing some building in the midst of existing housing could reverse this spiral and breathe life back into communities.’

But estates are not the only place where he feels building opportunities are being ignored.

‘People say there’s no land. But there’s lots and lots of land. Look at the amount we use for car parking. Why should we give over so much space just for cars when with imagination it can be used for housing too?’

He points to a development in St George, Bristol: Hope Rise, where 11 zero-carbon social rent flats now sit on a steel podium above what was and remains a public car park.

The same could work on other Bristol car parks, he thinks, with little or no visual impact and no loss of parking spaces.

He would like to see councils, elected members and developers being more willing to experiment and more tolerant of failure. ‘Too often the response is let’s bulldoze what’s there and start again but it’s much better to work with what we’ve already got. We need to be more open to taking a punt on a new idea and, if it’s not an immediate success, ask “Can we do something that will make this work” rather than give up’.

Challenged to name the actions he’d like Bristol to take to find smaller scale solutions to its housing challenges, he reels off five:

- As a major landowner in the city, the council should make more land available at peppercorn prices for interesting, small schemes, thinking less about profit and more about progress.

- There should be a city wide approach to mapping areas where certain issues might arise – e.g. biodiversity hotspots or sites of likely archaeological interest – so that all would-be developers can see at one glance which site problems need full investigation.

- Planning rules and regulations should be more open to a greater diversity of ideas.

- Speedier processing should be offered to small builds/ self-builds.

- Politicians off all parties need to tone down their tribalism.

In a year which will see local council elections and a parliamentary election, he sees the latter point as especially important for the future of housing.

‘If your party is the ruling administration, the opposition is always looking for ways to say you’ve failed. This leads to fear of blame and a low risk culture which infects the whole organisation. Leaders need to be upfront. “I’m going to try some stuff and I’m not always going to succeed”. Opposition needs to accept that failure is often necessary to achieve progress because it provides lessons which can lead to success.’

Paul Smith will be one of the speakers when Bristol Ideas hosts a day-long event on Tuesday 23 April titled Re-imagining Public Administration: the Creative Bureaucracy Day. He will be in discussion with Melissa Mean from We Can Make. For more information and details of how to book, click here.

Pam Beddard is a writer and publicist based in south Bristol whose work credits include devising and delivering campaigns for the Avon, Somerset and Wiltshire Wildlife Trusts, the Countryside Agency, Forestry Commission England, the Natural History Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition, the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, Whitley Fund for Nature, the Woodland Trust and several overseas-based wildlife conservation NGOs.

Paul Smith is CEO of Elim Housing, a charitable social landlord based in Bristol. He previously served as a Bristol City Councillor from 1988 to 1999, when he was chair of the Environmental, Health, Land and Property and Leisure Services committees, and 2016 to 2020 when he was Cabinet Member for Homes and Communities.